Chida joined Seiko in 1986. After designing watches for international markets, he expanded his expertise to include electronics, communications equipment, and related industries. Currently, he is focused on advanced design development.

Masayuki Nakamura

After working for an in-vehicle device manufacturer and a major electronics company, Nakamura joined Seiko in 2008. He now specializes in software development for quartz watches, including the Prospex and WIRED brands.

Chida joined Seiko in 1986. After designing watches for international markets, he expanded his expertise to include electronics, communications equipment, and related industries. Currently, he is focused on advanced design development.

Masayuki Nakamura

After working for an in-vehicle device manufacturer and a major electronics company, Nakamura joined Seiko in 2008. He now specializes in software development for quartz watches, including the Prospex and WIRED brands.

What we wanted to convey at Seiko Seed

Chida: Seiko has always aimed to connect with watch enthusiasts, but I felt there was more we could do to engage those who aren’t initially interested in watches or believe their smartphones are sufficient. This idea sparked the creation of a hub for sharing information and broadening our reach.

Nakamura: I felt that if we could showcase these fascinating yet little-known technologies in an engaging way, it would spark people’s interest in watches themselves.

Chida: Seiko Seed carries multiple meanings—it is a place where people can experience the joy of watches, a platform for sharing technology and design, and a space for sowing the seeds of the future. The word “Seed” also serves as an acronym for Seiko Experience Engineering and Design.

Nakamura: A watch is one of the most familiar “machines” in daily life, yet most people rarely have the opportunity to observe the mechanisms behind the movement of its hands or the sounds it produces. With Forest of Mechanisms, the first exhibition at Seiko Seed, I wanted to create a space where visitors could experience the intricate mechanisms, fascinating details, and technological depth of watches—brought to life through the graceful movement of their delicate hands and the beautiful sounds they produce.

Chida: Forest of Mechanisms consists of two main installations. The installation Forest of Clockwork was produced with artist Ryota Kuwakubo*1 as an external advisor. The installation Watches That Forgot Their Role was developed collaboratively based on a project proposal by nomena.*2

Nakamura: Among Seiko’s many timepieces, the watches we highlighted this time were the metronome watch and the digital talking watch, as they feature unique technology distinct from that of conventional watches. Notably, both have been recognized with the Good Design Award.

Chida: As the name suggests, the metronome watch is a watch equipped with a metronome function. Unlike a typical watch, where the hands move in unison, this timepiece features a unique internal mechanism that allows each hand to move independently, offering greater flexibility in expression.

Nakamura: I also saw the potential to use the digital talking watch’s function to audibly convey the time to people with visual disabilities and decided to feature these two watches, as I believed they would offer a more engaging experience.

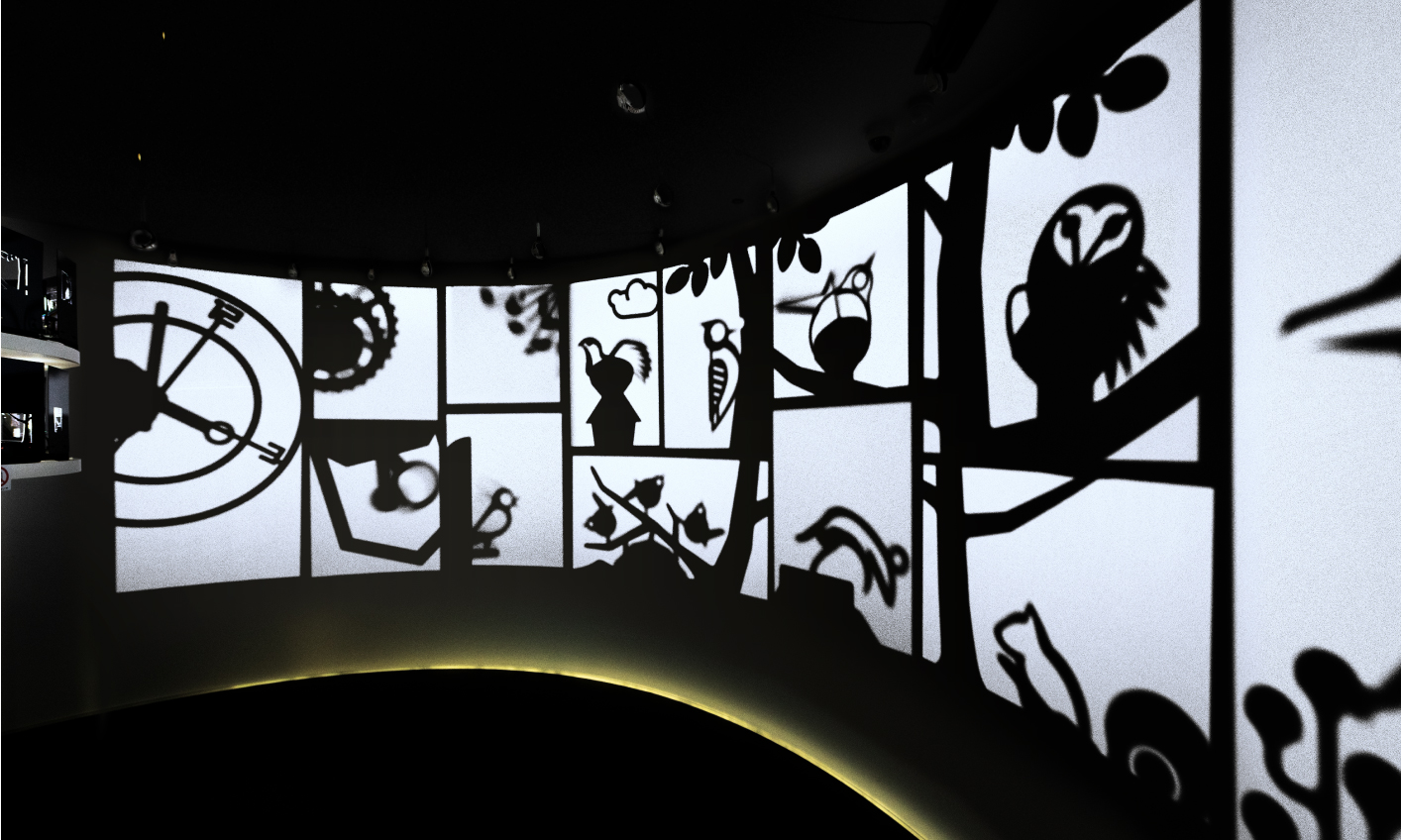

The Forest of Clockwork—created by connecting intricate, minute technologies

Chida: The concept for the Forest of Clockwork began with the idea that shadow puppets might be an effective way to show the movement of the tiny mechanisms inside a clock in a bold and easy-to-understand way.

Chida: When considering what I could convey through shadow puppets on the theme of time, I envisioned the first encounter between people and time. I imagined that early humans must have sensed it through the sounds of birds and insects in nature, and the daily cycle of dawn and dusk… From this inspiration, I developed various shadow puppet motifs.

Nakamura: That said, we initially lacked the know-how to project shadow puppets, which led to many challenges during development. We created an experimental model, but at first, we couldn’t even get the shadows to appear as we envisioned. Ultimately, we were able to bring the Forest of Clockwork to life using the internal mechanisms of 16 special timepieces and 16 digital talking watches.

Nakamura: The digital talking watch was suspended from the ceiling and functioned as a speaker. The sounds it played transitioned from the tracking of the time to animal noises and the ticking of the hands. However, the basic functionality of the digital talking watch was retained almost in its entirety.

Chida: The sounds were surprisingly quite clearly audible, without any distortion.

Nakamura: That’s right. However, digital talking watches were originally designed to announce the time using a human voice, making it easy to hear. It was challenging to adjust the lower-pitched sounds, such as the hooting of an owl, to make them more easily audible.

Chida: The owl was especially popular with children. We carefully considered the movement of each creature, designing the exhibit so that their movements would bring the shadows to life.

Nakamura: It wasn’t enough for them to simply move from side to side—they had to feel truly alive. Capturing that in the programming was quite a challenge. As for the movement of the watch hands, in watches of the past, the hands would shift back slightly each time after moving forward, and we faithfully recreated that motion as well.

Chida: I’ve heard that adjusting the movements of each of the 16 pieces required as much effort as creating 16 entirely new products. Although I feel rather apologetic for the considerable trouble we caused, I was truly impressed by the exceptional quality of the finished work.

Nakamura: Visitors initially thought it was an animated film and didn’t realize it was a shadow play. When I revealed to them the secret that “Actually, this is a shadow play operated directly by clock mechanisms,” their reactions where quite remarkable. They were surprised by the contrast between the traditional art of shadow play and the precision of mechanical engineering. We meticulously calculated both the timing of the sound and the movement, and I was delighted to receive praise for this from both inside and outside the company.

Chida: In terms of direction, Mr. Kuwakubo’s supervision was a significant aspect of the project. He provided valuable insights into screen composition, making the presentation even more compelling. On a more detailed note, the main character of the exhibition was the misosazai, or Eurasian Wren, a bird often featured in fairy tales and depicted as small yet bold.

Nakamura: The purpose of this exhibition was to showcase the remarkable ingenuity of small-scale internal mechanisms, and I found the wren to be the perfect symbol for this.

What emerges when a watch abandons its function – Watches That Forgot Their Role

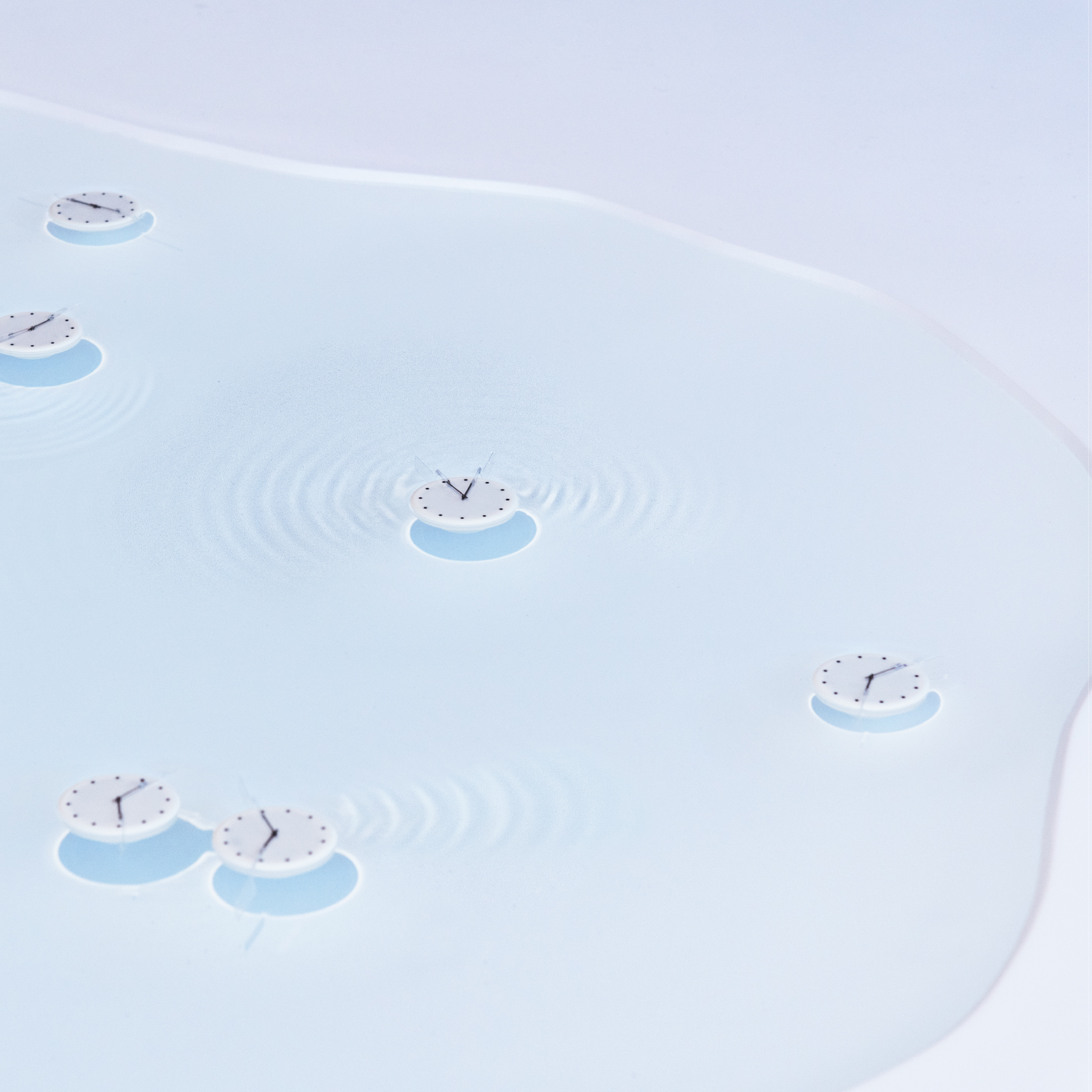

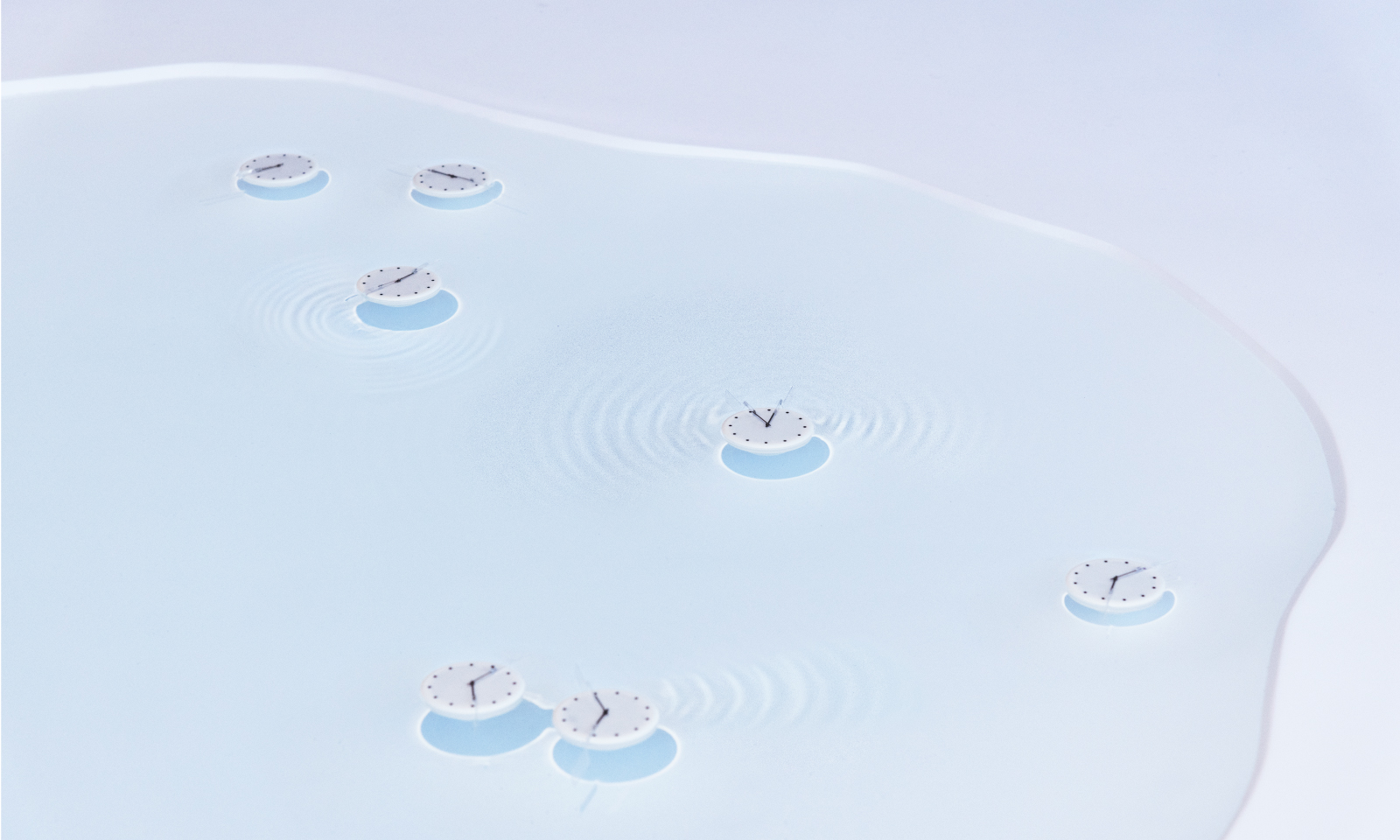

Chida: In the installation Watches That Forgot Their Role, we explored three motifs: water striders, butterflies, and raindrops. Abstraction, the concept behind this exhibit’s title, is a way of understanding the essence of something by discarding certain characteristics while preserving others. This work is based on the idea of what remains when we deliberately set aside what is often considered the essence of a watch—its ability to measure time.

Nakamura: This work was created in collaboration with the external creative group nomena. In particular, Watches That Forgot Their Role #1—a buoyant watch with a water strider motif that advances by moving its hands as it glides across the water—is an idea that only nomena could have conceived. As a company specializing in watches, we would never think of floating a precision instrument on water.

Chida: Then, there was the metronome watch. I felt its movement had a sense of vitality, which led me to wonder if it could be made to move like a real insect. However, I never imagined it would actually be possible—until I saw how attaching fins to the hands brought it to life. I was completely surprised.

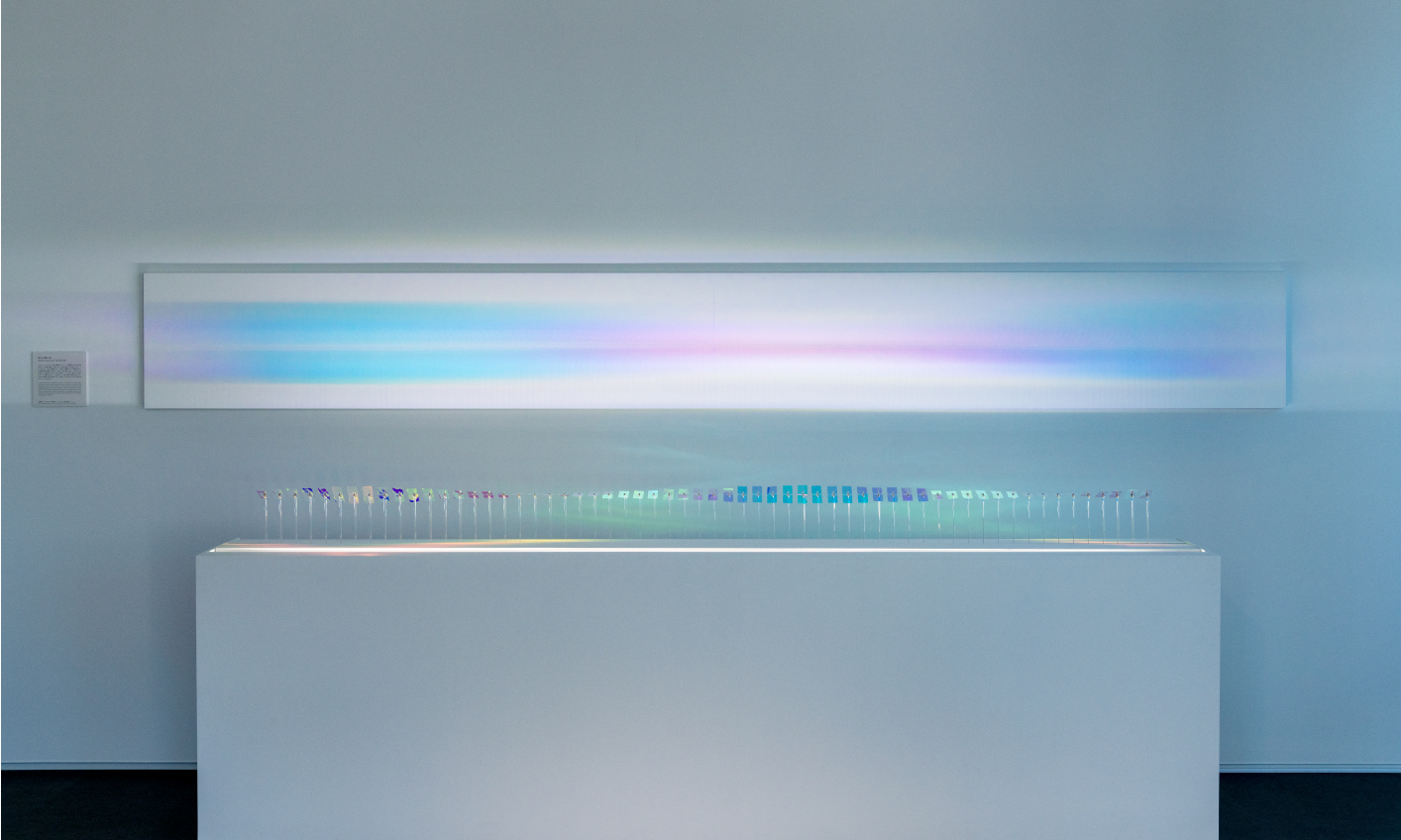

Nakamura: The display that adorns the watch hands with colorful wings, making them flap like a butterfly (Watches That Forgot Their Role #2), is made possible by a specialized internal mechanism that allows the hour and minute hands to move freely.

Chida: What was surprising was that, for our collaborators from nomena, creating an exhibit using only a tiny, quiet watch mechanism was a refreshing experience. For us, it was a revelation that something so familiar to us could be unexpected and fascinating to others.

Nakamura: In Watches That Forgot Their Role #3, which takes raindrops as its motif, we sought to express the passage of time through a scene of drizzling rain, depicted by drops of light and the sound of rain, along with the subtle changes that unfold. The occasional notes of a piano further enhance the atmosphere. In this work, the drops are counted on the watch’s liquid crystal display.

Chida: In fact, the same technique used for the LCD display was harnessed for the digital talking watch that hung in Forest of Clockwork.

Nakamura: That’s right. We used the counting function to express the sense of time and the pulse speed of each creature appearing as shadow puppets. While not much was visible in the dark space, I’m glad we could be so meticulous about even these subtle details.

The future potential of Seiko’s technology and design

Nakamura: For this exhibition, we took an agile approach to design and development— conceptualizing, prototyping, testing, and refining through multiple iterations. This process allowed us to remain flexible and responsive to the requests of the design department.

Chida: I am truly grateful for your ability to accommodate our detailed requests. This exhibition reaffirmed Seiko’s capacity to share a broad range of ideas, while also highlighting the great potential of the Seiko Seed space. Some visitors stayed for more than two hours, while others eagerly inquired when the next exhibition would be held, which was incredibly encouraging.

Nakamura: I was pleasantly surprised by the large number of visitors, spanning a wider age range than expected, including many families. Given that the venue was in Harajuku, I had assumed the visitors would primarily be young people. In the end, I believe we succeeded, at least to some extent, in our goal of expanding the Seiko fan base.

Chida: Through initiatives like this, we aim to continue sharing a diverse range of insights, not only about watches but also about the broader context surrounding them. We hope you look forward to future updates from Seiko Seed and Seiko!

*1 Ryota Kuwakubo

Artist / Professor at Institute of Advanced Media Arts and Sciences (IAMAS) / Part-time lecturer at Tama Art University’s Department of Information Design

After studying contemporary art, he created BITMAN in collaboration with Maywa Denki in 1998, and began creating works using electronics. He has created a unique style of art, also known as “device art,” through his works that take a close-up look at events occurring at various boundaries, such as digital and analog, human and machine, sender and receiver of information, etc. His representative works include Video Bulb, PLX, and Nikodama. Since his installation The Tenth Sentiment in 2010, he has been working on works that allow viewers to weave their own experiences from within. He also works as an art unit, Perfektron, and was involved in the exhibition structure of Design Ah! Exhibition (2018 / Toyama Prefectural Museum of Art and Design, The National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation, Japan).

*2 nomena

Established in 2012, nomena implements concrete mechanisms for unprecedented manufacturing possibilities, powered by the multidisciplinary knowledge we continue to learn through daily research, experimentation, and collaboration with creators and clients.

We are a group of engineers who believe in making things because they are impossible, because they have never been seen before, and because they do not yet exist in the world.

In recent years, nomena has participated in joint research with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and other research organizations, and in the mechanical design of the Olympic torch for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. Major awards include the Excellence Award in the Art Division of the Japan Media Arts Festival (2022), the Pen Creator Awards (2021), the DSA Design Award Gold Prize (2017), the Japan Sign Design (SDA) Award of Excellence from Japan Sign Design Association (2017), and the Bloomberg Pavilion Project Grand Prix at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (2012).